A common quip about nuclear fusion is that the technology is perpetually 30 years from deployment. Fusion research has not been funded to the same levels as other, already-realized clean technologies like solar, wind and fission, but new billion-dollar investments signify interest is picking up.

University of Wisconsin-Madison fusion spinoff company Type One Energy aims to bring nuclear fusion to the grid within a decade, backed by funding and a physics-based model.

In March, Type One Energy published a series of six papers in the Journal of Plasma Physics outlining their model for the plant, and have partnered with the Tennessee Valley Authority utility company with plans to build the plant by 2035.

In an interview with The Daily Cardinal, Chris Hegna, a University of Wisconsin-Madison nuclear engineering professor and co-founder of Type One Energy, described the science behind fusion reactors and how he helped design the fusion plant. Hegna, who leads Type One Energy’s physics optimization group, is known for pushing forward the design of stellarators, contributing heavily to UW-Madison’s Helically Symmetric eXperiment (HSX).

The background behind fusion

Fusion’s reaction mechanism makes it an essentially limitless carbon-free technology with the potential to be hundreds of times more energy-efficient than wind, solar and hydroelectric energy. Unlike other forms of renewable energy that produce different amounts of energy depending on the weather, fusion would provide a consistent and steady supply of energy, making sizing transmission lines easier and reducing the need to build expensive energy storage units.

Fusion starts with two hydrogen-based atoms, commonly deuterium and tritium. Deuterium is abundant in seawater, but tritium is not, and producing it will be a critical part of any fusion plant’s machinery, Hegna said.

In nuclear fusion devices, deuterium and tritium atoms combine to create a helium atom and a high-energy neutron. The neutron shoots into the wall of a fusion device, generating heat that the device transforms into electrical energy.

A fusion reaction can only occur within a plasma, essentially a very hot, electrically charged gas. Type One Energy’s stellarator is a magnetic confinement design, meaning it uses magnetic fields to keep the plasma hot enough — around 2 million degrees Celsius — and pressurized for a long period of time so the deuterium-tritium fuel can react. The fields keep the plasma from touching the reactor walls and losing heat.

A successful fusion reactor requires initiating the plasma conditions and running a “steady-state” operation, made possible through containing the plasma’s energy and preventing it from escaping into the walls of the fusion device.

Infinity Two would achieve a “burning plasma” state where after an initial energy input at the startup stage of the device, hot plasma would remain hot, self-sustaining future fusion reactions. This would allow the device to create more energy out than energy in, which is necessary for fusion energy to be commercially viable.

“In today’s devices, since we don’t have any fusion going on, we inject power,” Hegna said. “Burning plasma means that self-heating dominates the external [power] sources you put in there.”

Running HSX, UW-Madison’s fusion design experiment

After completing a PhD in plasma physics from Columbia University in 1989, Hegna joined UW-Madison’s nuclear engineering and engineering physics department as a faculty member. There he met ECE professor David Anderson, who designed the magnetic confinement facility running at the Helically Symmetric Experiment (HSX) laboratory in UW-Madison’s Engineering Hall.

Though the tokamak was the leading fusion reactor design at the time Hegna began his study of fusion, it came with a significant challenge: creating a magnetic field in a tokamak required running a current directly through the plasma. This could cause the plasma to become unstable, Hegna said. Additionally, electromagnets driving the current through plasma in tokamaks need intermittent resets, which shut down the device and limit power output.

Instead of the tokamak, Anderson and Hegna focused their research on the stellarator, which does not use a solenoid. The stellarator is a fusion device design that has existed since 1951, described as fusion energy’s “dark horse” compared to the tokamak.

Compared to the tokamak, the stellarator appears more organic: a magnetic field is induced through twisted, writhing curls surrounding the inner walls of the confinement vessel. The plasma inside of the vessel no longer carries current.

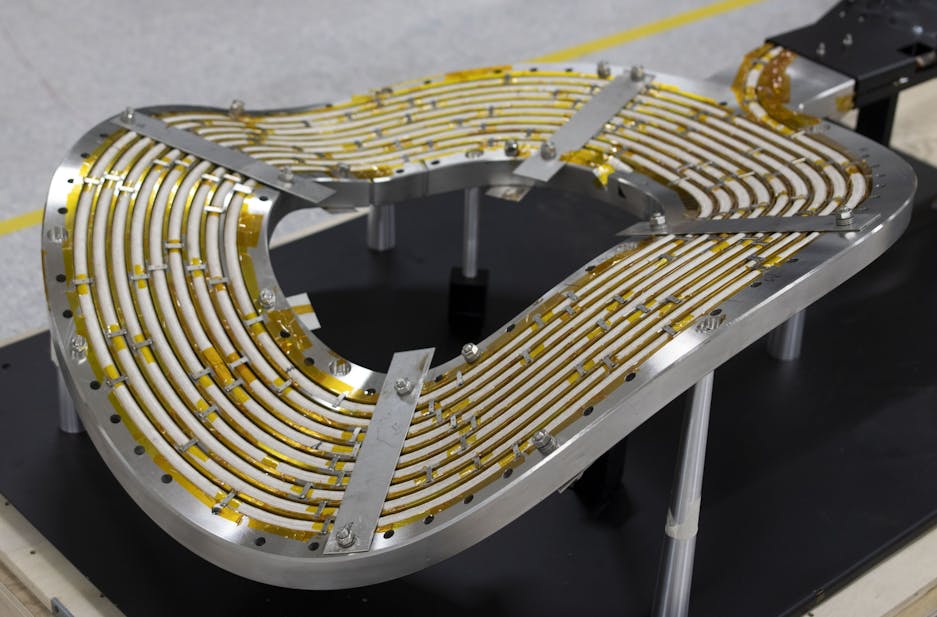

An individual stellarator magnet.

Though a stellarator design eliminates the need to induce and control a current through plasma, it introduces different challenges — the coils require precise engineering.

“In principle, the stellarator has all the nice confinement advantages that you get in the tokamak without the necessity of coming up with exotic systems for producing plasma current,” Hegna said. “The harder part is that all the onus now is on the design of the external magnetic fields.”

Tokamak research was funded over stellarator research in the 1960s because of the tokamak’s higher ability to confine plasma. As long as plasma particles face minimal friction, they keep moving in a circular path around the symmetric, donut-shaped tokamak. In a stellarator, which is asymmetrical, plasma particles are more likely to escape.

Hegna said that in poorly designed stellarators, deuterium and tritium particles simply “leave” the confinement volume where fusion is possible. In these stellarators, even if plasma can be heated to the temperature required for fusion, the plasma particles exit so quickly that a fusion reaction is impossible.

But in the 1980s, fusion scientists discovered new ways to manipulate the shapes of a stellarator’s coils that better confined plasma particles and allowed stellarators to compete with tokamaks. HSX was born from one of these designs: Hegna said plasma particles can still ‘see’ symmetry in the magnetic field created by its asymmetric coils.

“The idea was to impose this notion of a [quasi-]helical symmetry, not a true symmetry, into the device and use that as the underpinning optimization principle for the device… this was a big breakthrough,” Hegna said.

Infinity Two builds on HSX research

The idea of stellarator optimization kept “building and building,” Hegna said. Eventually, a team of German researchers used a related concept called “quasi-isodynamicity” to design, build and operate Wendelstein-7-X (W7X), the world’s largest stellarator located in Germany.

W7X recently achieved the record continuous time for producing a fusion-type plasma: 43 seconds. Infinity Two, Type One Energy’s fusion reactor design, will be bigger and, according to Type One Energy’s physics-based models, better.

“The success of HSX and W7X, as well as the continued evolution of our computational modeling culminated in these papers that we wrote,” Hegna said. “We took the world’s best code, the world’s best data, and asked, ‘Can we use that to inform our design?’ That was the idea of Infinity Two.”

A rendering of TVA’s Bull Run Energy Complex near Oak Ridge, Tenn., the future home of the Infinity Two fusion power plant.

The Infinity Two stellarator model used data from HSX experiments along with decades of data and “high-fidelity computational models” from the fusion community. By comparing their own data from HSX experiments to the outputs of different models, Hegna’s team could choose which models were most accurate for simulating Infinity Two.

Before Infinity Two’s construction, Type One Energy plans to construct a smaller fusion plant called Infinity One by 2029. Infinity One will not be a fusion device; it will primarily be built to “demonstrate the physics [Type One Energy is] trying to affirm,” Hegna said.

Infinity Two is still a design, not a finished plant. But Type One Energy’s peer-reviewed, physics-based model and utility partnership reduces some of the uncertainty keeping fusion perpetually 30 years away.