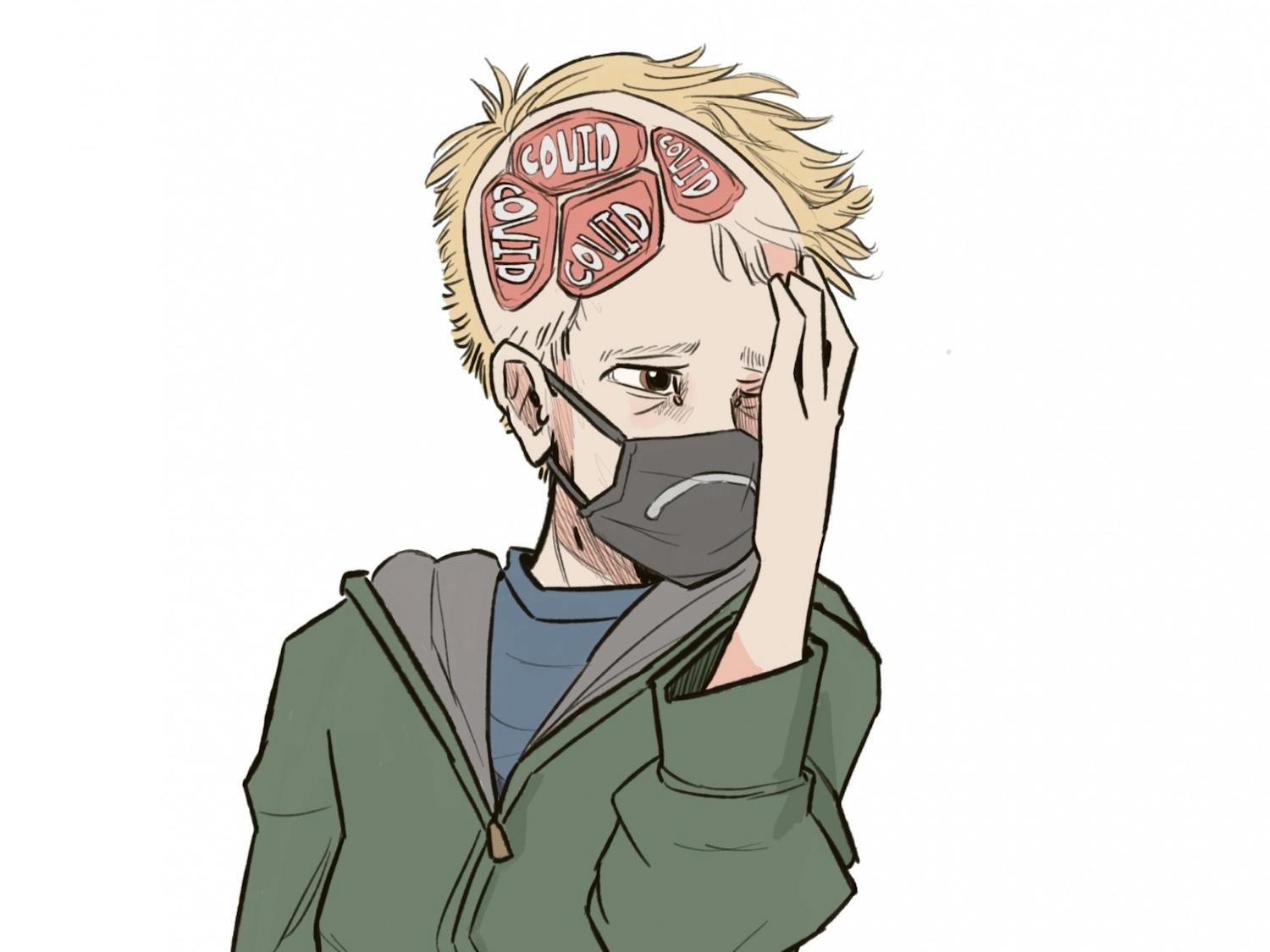

Student struggle with homelessness exacerbated by COVID-19 pandemic

By Karissa Schumacker | Mar. 25, 2021“Online school is our home. Where we live is our classroom right now, this is where we're learning... what will happen to people who can't pay for housing?”