Twenty percent of women will be sexually assaulted at some point in their lives — but that number jumps to 45 percent when applied to Native American women, according to the National Sexual Violence Research Center.

Native American women have been at higher risk for crimes related to sexual violence for decades now, across the country, state and on college campuses.

Despite the innate relationship between Wisconsin land and Native American communities, the UW-Madison participated in the Association of American Universities Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Misconduct for the first time in 2015. The results showed close to 50 percent of Native American women on campus have experienced some form of sexual violence.

UW-Madison took part in the AAU survey for a second time in 2019, releasing its findings in October. The results reflected similarities to 2015 — and even an increase in some percentages related to Native American women.

This year, 66 percent of American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander females on campus experienced sexual harassing behaviors; however, not enough women in the category reported sexual assault for a percentage to even be calculated.

Barriers in data collection

When considering absent percentages, some technical factors come into play, like changes in the survey questions from 2015 and also the sample size of the indigenous population on campus compared to total students.

Native American students made up less than one percent — 0.95 percent exactly — of the student body for the fall 2019 semester, according to the Office of the Registrar.

Nonetheless, similar findings to the UW-Madison AAU survey highlighting the discrepancy between experiencing and reporting sexual assault parallel other university campuses, reservations, work environments and cities across the country.

And these numbers probably aren’t fully representative of the actual rate Native American women experience sexual violence as they often don’t report to authorities, according to Megan Thomas, communications specialist with the National Sexual Violence Resource Center.

“What we know is that there are a lot of barriers in place for any survivor of sexual assault to come forward, but there are some that are even more specific to Native American survivors,” Thomas said. “One of the things we hear about is historical trauma: this collective injury on a population that can carry across generations. Those memories, those events, those traumas will be passed down through generations and can lead to distrust of law enforcement.”

Even when women do report, Thomas stated that Native American communities can experience geographical barriers, like lack of access to law enforcement or medical care.

The university has expanded its resources for students in the past decade. There is now a department in University Health Services dedicated to violence prevention, a designated Title IX coordinator position and new requirements for students.

But the rates persisted.

Perpetrators and jurisdiction

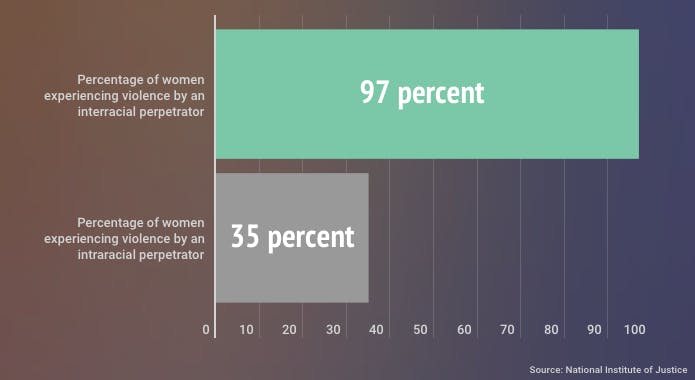

There are various factors in addition to lack of trust with law enforcement that keep women from reporting their experience. Thomas stated that another hindrance has to do with the perpetrators, who are mainly white.

While 35 percent of Native American women experience violence from other Native Americans, that number increases to 97 percent when considering those who experience violence by an interracial perpetrator, according to the National Institute of Justice.

“Perpetration by people outside of Native communities against people in Native communities is common, which is the reverse of any other sexual violence,” Thomas said. “That's a whole other element [of] that continued marginalization.”

Native women experiencing these crimes at a higher rate than other racial and ethnic groups is not a coincidence, it’s an epidemic, according to Samantha Skenandore, member of the Ho-Chunk Nation and lawyer in service to tribal nations for the past 15 years.

Skenandore, who focuses her practice on both federal Indian law and tribal law, has represented 80 sexual assault victims, most of whom were indigenous clients. Of those, 78 were women.

“Most cases I've worked on involves a white male on tribal territory assaulting a native woman,” Skenandore stated. “It's almost always that case. And how do you stop it? Well, who are the perpetrators and where are the crime taking place? Because that defines [the] jurisdiction — and then you know what programs and services are needed.”

Crimes committed against Native American women on the UW-Madison campus are taking place on land that belongs to the Ho-Chunk Nation. And that’s why jurisdiction matters.

Wisconsin is one of six states in the country that allows for state government control over offenses committed against American Indians on tribal land, according to Public Law 280.

Not only does this complicate the relationship between tribe and state, which have historically competed for resources within tribal land, but it can also produce unique barriers to Native American women seeking help from a criminal justice authority on tribal lands, Skenandore said.

“It's a crazy political game of trying to keep tribal sovereignty as minimal as possible, and also trying to have state law apply in tribal land,” Skenandore said. “In federal Indian law, [a] large premise is that the federal government has a responsibility to take care of tribal nations — states are generally not allowed in that relationship.”

When PL 280 was put in place in 1953, it granted states broad criminal jurisdiction. But that control remained concurrent with tribal criminal jurisdiction.

While state government and tribes battled for authority, the federal government saw the law as a way to drop financial and technical support for tribal resources in designated states — like on all reservations in Wisconsin, except the Menominee Territory.

According to Skenandore, due to lack of federal dollars and a general absence of state support, many tribal court systems have failed to function as well as they could. Many American Indian Nations in Public Law 280 states still do not have functioning criminal justice systems.

“If I laid out for you what the sexual assault, domestic violence laws look like in the seven jurisdictions that I'm barred in, you'll see them look pretty different because they're all in different phases of governance,” Skenandore said. “Everybody assumes tribal courts are all the same and they're not. They can be like a baby in diapers or they could be the old wise man.”

The power of cultural healing

Kristin Welch is a community organizer with Menikanaehkem, a nonprofit on the Menominee Reservation, who works on several initiatives: food sovereignty, solar power, language and culture revitalization and with a women’s cohort focused on healing.

Welch stated that violence against Native women began with colonization. And while we might not see the repercussions of this in a traditional sense, that oppression hasn't disappeared, it's just integrated into new systems.

"It's almost ingrained in every part of our lives, this violence against us," Welch said. "And the jurisdictional issues don’t help, they make us an easy target.”

Additionally, she explained other barriers for Native American women, like how seeking help from agencies and institutions remains stigmatized and the minimal policing on tribal land.

The Menominee land is the only reservation in Wisconsin not subject to PL 280, meaning the federal government still provides tribal courts with resources, both monetary and occupational. Still, it's difficult to process non-native offenders because they get lost within the system or it takes too long, according to Welch.

Welch stated there is a cycle of oppression Native women face that requires a greater fix than jurisdictional correction or an increase in cultural awareness. There is inequality built into the system.

When Welch met with other Native women in her community, they realized they all had experienced sexual assault or domestic violence at some point in their lives. From there, they figured out how to move forward together.

“We have to first heal ourselves and address our own trauma before we can help other people,” Welch said. “We rely on our culture for that. And that's where the empowerment comes from, understanding we have all the tools to heal, all the tools to organize and empower women in our culture and original language.”

Moving forward and shifting responsibility

Both Welch and Skenandore agreed that it’s important to society — as well as college campuses — to examine how indigenous women have been portrayed over time.

“We're hypersexualized, so we have to deconstruct that image and that idea in Western Society because it is dangerous,” Welch said.“The focus should be on educating offenders and holding them accountable, first and foremost. That should be a campus responsibility.”

And while UW-Madison and schools across the state have committed to developing more cultural awareness — emphasizing the UW System’s desire to develop relationships with sovereign Nations and acknowledge traditions, beliefs, governance, laws, codes and regulations — Skenandore says it’s not enough.

In this year’s AAU survey, indigenous students had the least amount of trust the university would conduct a fair investigation, not even registering a percentage in the final data. Thomas stated that historical trauma could be a potential explanation.

Despite this, Skenandore sees an opportunity for institutions to do more.

“We have so much persuasive power with adolescent people to tell them what they are and what they aren't,” Skenandore said. “And it's the same thing with all of these people that can be doing things like the chancellor and the student government. The university is a great place to make a long-standing change because these are all future leaders.”

For Welch, the opportunities to fight injustice against Native women are not few and far between; they are powerful reminders of the resilience of indigenous populations and can be carried across college campuses and the nation.

“My uncle had always said that we were perceived as remnants of war — and we are,” Welch said. “But we're also incredibly resilient and strong. Every attempt to destroy us failed and that’s incredibly beautiful and empowering.”