High school is a fundamental aspect to every student’s education.

Not only does it constitute the time individuals can find their passions, but it prepares them for a path they choose to travel beyond graduation, be this higher education, the workforce or service. However, the institution of high school comes with its challenges, specifically in terms of how schooling is structured and its subsequent effects on students.

While systems of education are often put in place to benefit students, they can end up harming students of marginalized populations like female students, those coming from low-income backgrounds and students of color.

Tracking in Schools

Though some schools begin to track students as early as elementary school, the largest gaps in student learning arise through tracking systems in high school.

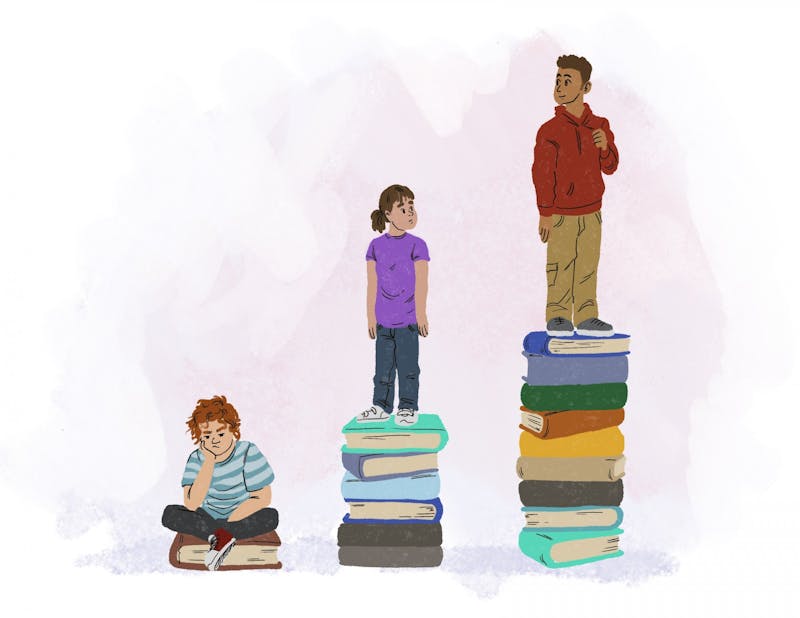

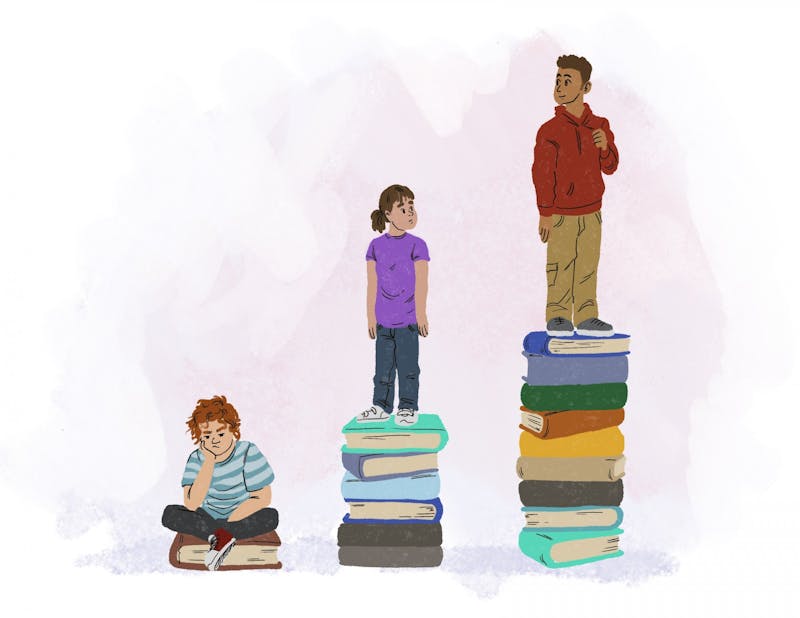

Tracking — the concept of assigning students to differing groups, often with different curriculums that are more or less rigorous — has been a widespread method of schooling aimed at personalizing education to students and their individual academic ability. Having been part of school curriculums for decades, the tracking system is now ingrained in the culture of secondary education.

A generic model of tracking reflects two tracks: the Honors/Advanced track includes students perceived to be high-achieving who can learn at a quicker pace and can be challenged with more difficult course curriculum, while the Regular track includes students who are perceived to be average and require a slower pace to learn concepts.

Some schools even implement a third track for students who may need extra help to grasp course materials and require a slow pace to learn. Though they are never labelled as such, students tend to know which track is which, simply by looking at the students in each.

On paper, the system seems appropriate to address the differences in how students learn and acquire knowledge. By pacing the curriculum at different levels, students can learn the same material in a personalized manner. Students with different motivations are also accounted for in this ideal system of level-based education. Even teachers in schools can focus their time and energy on a standard set of students at a time, rather than aiming to fulfill the needs of a variety of students with differing levels of interest and capability in the same classroom.

Ideal types, however, are rarely executed in a neutral manner. Being a system implemented by humans, it is quite obvious the application of tracking in schools will be subjective — prone to implicit biases and prejudice.

Some students from the greater Madison area acknowledged the ways in which tracking systems work to influence schooling and students’ lives, often segregating them from each other in their learning.

A former student of a Madison-area private school, who chose to remain anonymous for privacy concerns, explained the system of tracking in their school, emphasizing how notable disparities were present between the honors track and regular track subjects, all under the school’s International Baccalaureate (IB) program.

“STEM subjects were better developed than humanities subjects at my school. It was easier to pass History and English, and I was interested in English and History in high school. Because it was lower prioritized, it was easier work,” they said.

These effects of tracking, then, move beyond the systems placed in public schools, for even students in private institutions feel the discrepancies tracking creates. The aforementioned subjective versions of tracking are apparent through the ways in which subjects are favored by school administration, what tracks themselves are preferred by both students and teachers, as well as teacher-student dynamics in school.

“Honors section teachers were more popular. They weren’t necessarily easier on students, but they engaged with students in more interesting ways and ultimately knew us better,” the student explained.

The use of tracking systems, then, exhibits the political nature that education assumes — whether this be what subjects have the most resources, most student interest or what teachers instruct the classes.

Schooling, which is first and foremost a resource to inform young people and impart them with knowledge, becomes a battleground for different players at stake, and this competition largely originates from systems like tracking.

Beyond these direct impacts on students’ education, research has overwhelmingly confirmed the socially biased nature tracking methods entail. According to The Brookings Institution, such school practices don’t just mirror inequalities that are present at the larger, societal level, but work to reproduce and perpetuate those same inequities.

Tracking systems are underlined by normative beliefs of class and race. Oftentimes, African American, Latinx and low-income children make up the lower and remedial tracks, while white, middle and upper class children constitute advanced and honors tracks.

Administrators and even educators themselves may defend the use of tracking in light of the heterogeneity of students and the need for individualized education to promote student achievement. It is quite clear, however, that protecting tracking systems, at least traditional versions, ultimately protects privilege and the status quo.

Standardized Testing

Similar to systems of tracking, standardized testing has its own set of negative effects on students, their education and overall outcomes.

Across the state, every student is intimately familiar with filling in bubbles and clicking on multiple choice questions throughout their primary and secondary education. We remember the stress these tests caused, as well as the emphasis many of our teachers put on them.

Standardized testing has been implemented in schools to assess student academic milestones, learning progress and the effectiveness of educators’ ability to teach. In Wisconsin, testing begins as early as third grade with the Forward Exams, which evaluate students’ progress with the Wisconsin Academic Standards.

While the Forward Exams can track students’ proficiency in math or reading, they cannot capture a crucial component of students’ performance: context.

“It’s frustrating because students’ performances don’t exist in a vacuum,” explained Abby Swetz, a former educator at O’Keefe Middle School.

Teachers are far better equipped to understand their students’ larger circumstances outside of the classroom when testing time rolls around each year. Life happens, and standardized tests can be extremely unforgiving when something unexpected arises.

“I had one student, who qualified for free and reduced lunch, come into school late after spending the night in his family’s car. He had no bed to sleep in, had no breakfast, and then we expected him to take this test at 9:15 in the morning,” Swetz said of one student’s testing experience.

And while standardized tests overlook these circumstances, they influence how students are tracked, and they help determine the trajectory of students’ entire academic experience.

Students from underprivileged backgrounds, including students of color and those with disabilities, are especially disadvantaged by these tests, much like they are by tracking.

Numerous studies illustrate a strong correlation between testing outcomes and socioeconomic status. Students from higher-income households often do better on standardized tests because their families have better access to educational opportunities and resources.

Wisconsin is notorious for its wide achievement gap between white students and students of color, and this is largely determined through analyzing standardized test scores. On the Forward Exams, for example, Black and Latinx students are far less likely to receive “proficient” scores than their white peers.

“Standardization is rooted in colorblindness and patriarchal structures that propagate homogeneity,” said Ananda Mirilli, a member of the Madison Metropolitan School District’s Board of Education.

Standardized testing is poised as an institution that solely determines a student’s ability within the academic realm, removing a person from their identities and circumstances. But this post-racial approach is precisely what is perpetuating academic — and eventually economic — disparities between students of color and their white peers. We need to recognize the systemic issues that hold students back and address these problems at their root; we can’t continue to ignore students’ contexts and humanity.

For as long as standardized tests are in place in their current form, students of color and students from low SES households are going to continue to be disadvantaged in schools — and we will only continue to unacknowledge the great benefit and knowledge every student brings to the table.

Where do we go from here?

While both of these fixtures within public — and private — schools are incredibly problematic, they do not have to remain the status quo of education.

All hope isn’t lost — some schools have approached tracking in less stigmatizing ways, one of which is at Middleton-Cross Plains High School.

Transitioning to integrated classrooms, MHS has begun to replace tracking. This system allows students to opt into “honors” level assignments while staying in the same classroom as the rest of their peers, meanwhile other students who do not want or are unable to meet that threshold don’t feel the stigma of being separated.

“You were in the same room during the classes as everyone else, it was just your homework assignments that were a little more difficult or you had one or two meetups outside of class,” said Reshma Gali, a former student of Middleton High School.

“Within the tracks themselves there wasn’t much competition because [honors tracks] were available to anyone who chose to try it. If everyone wanted the honors option, they could do that,” Gali said.

By integrating classrooms, students have the ability to succeed in personalized ways without the disproportionate effects on underprivileged students. For these exact reasons, it’s necessary to move education to not only be a more inclusive space for children and youth, but to ensure the system benefits everyone, not just certain groups.

Finding alternatives to standardized testing pose a greater challenge, but this is not an impossible task.

This effort would likely begin with the repeal of the No Child Left Behind Act, which federally requires standardized testing, or implementing new laws that would have the same effect as a repeal.

From that point, finding a way to collect data to inform decision-making in schools will require creativity and an understanding of what exactly we want students to gain from our education system.

Some schools around the country — such as those within the New York Performance Standards Consortium — have experimented with performance-based assessments to evaluate students over the course of their time in school.

This system empowers students to illustrate their understanding of what they are learning in the classroom in different applications. Likewise, schools and other entities can look at students in a more comprehensive manner under this system — certainly more so than a singular test allows.

Alternatively, an inspection approach could be implemented, such as the system in Scotland. Inspectors would sit in on lessons, examine students’ work, and talk directly with teachers and students.

A benefit of this approach is that it grants teachers the opportunity to be creative and flexible both in how they teach material and in how they assess their students — in turn, this allows students to develop their creativity and social skills, among others.

Finding new ways to better students’ educational experiences certainly requires dedication to research and policy change — overhauling the American education system as we know it is no small task. But just because it may be difficult to restructure our schools in a way that is equitable and beneficial for everyone doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.